In Brief

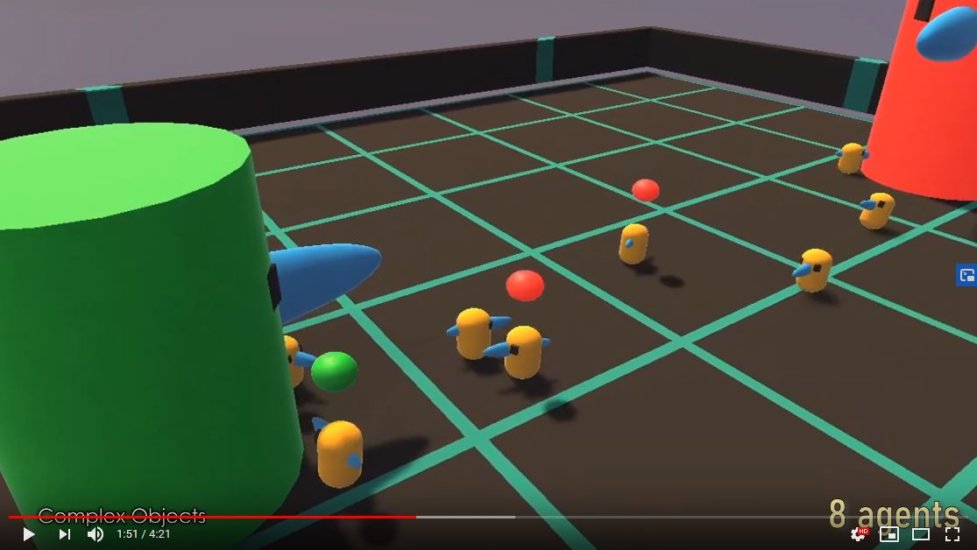

- I train agents moving in 2D to obtain objects, pass them to their neighbors, and deposit them in a box in such a way that the task is not possible without cooperation.

- I allow agents to learn slightly different policies by providing each with a unique one-hot encoded ID number as an observation.

- Statisically significant changes in individual behavior emerge during training but do not increase group performance on the task.

- The system scales well over modest increases in group size.

Intro and Concepts explored in this project

Learned behavioral modes directly linked to binary observations

In single-agent deep reinforcement learning scenarios, it is often beneficial to provide the agent with information on their internal state. In problems where the agent must learn to control the movement of its body in order to walk for example, the angles and relative positions of all its joints are given as an observation. A neural network model must then learn a mapping between this bodily configuration and an appropriate action effecting movment.

Observations based on “self-awareness” can be much simpler in fact. Agents trained with an observation vector including a binary state such as “I’m hungry = 0/1” can exhibit dramatic behavioral shifts when this state changes. For example, the agent may ignore a food source until im-hungry switches from 0 to 1, and it will then begin approaching it. In a previous version of the project described here, I found that providing agents information on the object they are currently carrying can cause them to exhibit completely different behvioral modes when this object changes. The information, called “item carried,” was represented as a one-hot encoding of three mutually exclusive states: {empty-handed, carrying item 1, carrying item 2}. When agents began carrying item 2, for example, they begin moving in the +x direction (Fig ).

This begs the question of what would happen if agents were trained using observations which include a one-hot encoded ID number (which is to remain fixed during inference.) Through training, will individuals evolve different behavioral sub-types as a result of perceiving this “ID state” in the same way that a single agent learns distinct behavioral modes?

Partially unshared neural network parameters

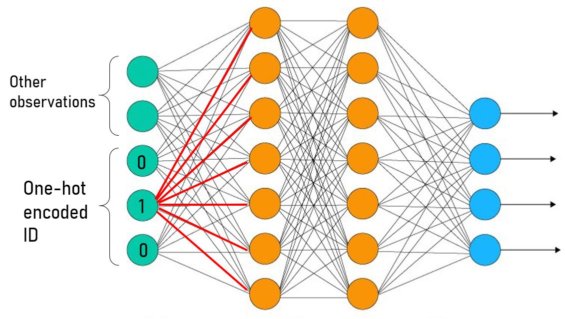

The inclusion of a one-hot encoded ID implicitly allows agents partially unshared neural network parameters in the first dense layer. An agent has exclusive access to a subset of weights in this layer (fig below). In the single-agent case, the influence of a single binary state is evidently enough to induce a different behavioral mode. This suggests that including one-hot encoded IDs may be sufficient to allow emergent behavioral differentiation through the process of training. In this project I assess the impact of providing each agent their own one-hot encoded ID number as part of their observation.

Fig. Red lines highlight the subset of weights available to an agent with ID=2 (of 3). During training and inference, no other agents will use these weights as that input node will be set to 0.

Fig. Red lines highlight the subset of weights available to an agent with ID=2 (of 3). During training and inference, no other agents will use these weights as that input node will be set to 0.

Obligatory vs. Emergent Cooperation

In multi-agent reinforcement learning and agent-based modeling, it is important to make a distiction between the (more interesting) “emergent” cooperation and what I would call “obligatory” or “prescribed” cooperation. This project uses the latter. I define emergent cooperation as cooperative behavior (agents working together to do a task) which has not been directly incentivized and is not absolutely required to perform well on a task. Obligatory cooperation on the other hand has been strongly incentivized, possibly using rewards that reinforce the cooperative act directly. My project directly reinforces cooperative acts using dense rewards and even makes such acts necessary in order to complete the task.

Reinforcement learning problem to be solved

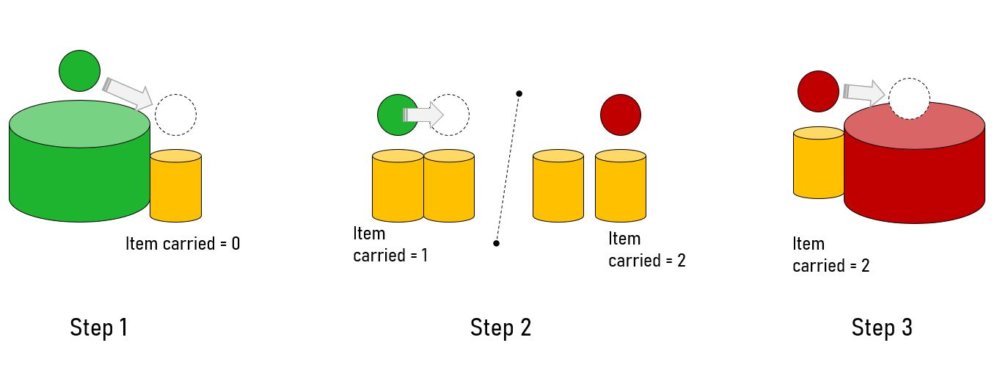

I train agents to acheive a group-level objective: transporting items across a space as fast as possible. The game is designed so that it requires cooperation to complete the task. Specifically, agents can retrieve green spheres (item 1) from the source box, but they can’t deposit them in the sink box themselves. Instead they must pass it to an empty-handed neighbor, who can then deposit it in the sink box. That is, only those who have received item 1 from a neighbor can deposit it. This is achieved by automatically converting the item 1 to item 2 when it is received.

To obtain item 1, pass it, and deposit item 2, agents must collide. The item transfer occurs at the same frame the collision occured. A reward of +1 is triggered by each of the three events and by no other collision types. In the case of passing, the reward is given to both the passer and receiver at the time of collison. Therefore, cooperation is not only required but incentivized directly. This contrasts with several works in multi-agent deep RL which achieve emergent cooperative behavior (ie without direct incentivization or requirement.) My study is directed more towards emergent diversity in a necessarily cooperative task.

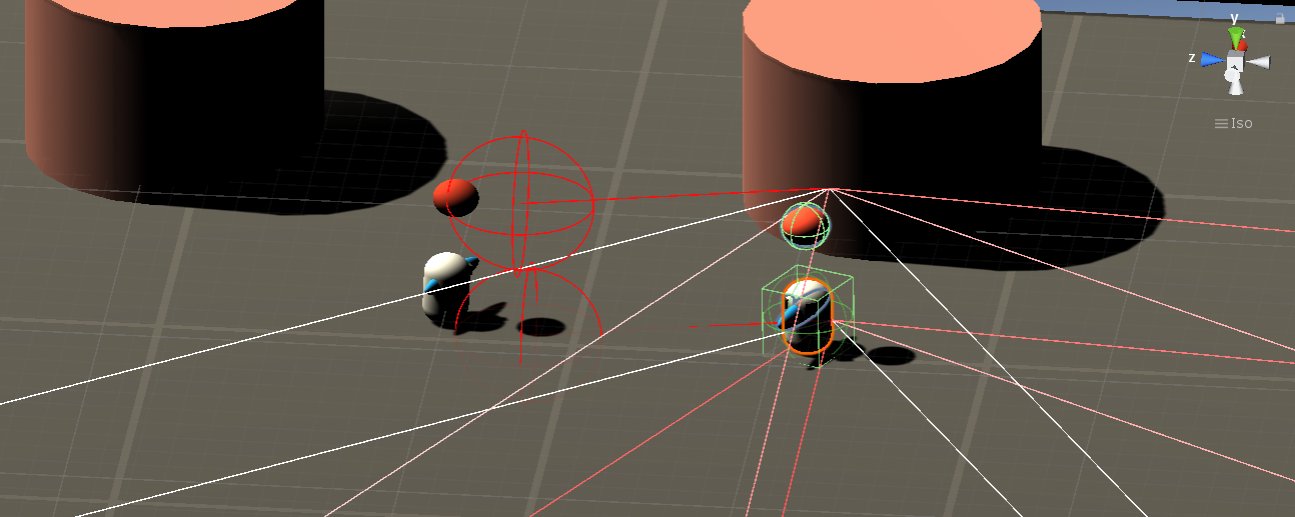

Fig. Agents (yellow cylinders) obtain and transfer items (spheres) at the moment of collision. An empty handed agent (item =0) must first retrieve item 1 from the source box (green). It can then transfer it to an empty-handed agent in step 2. The item will then self-convert to item 2 (red sphere). Finally the agent can deposit item 2 in the sink box (red cylinder)

Observations

Agents receive the one-hot encoded item type \(\{0,1,2\}\) that they are carrying \(V_{item-carried} \in \{0,1\}^{3}\). This is critical to include as it allows the agent to adopt different behavioral when their item_carried changes. In practice, sudden shifts in behavior are common when this part of the observation vector changes (see video).

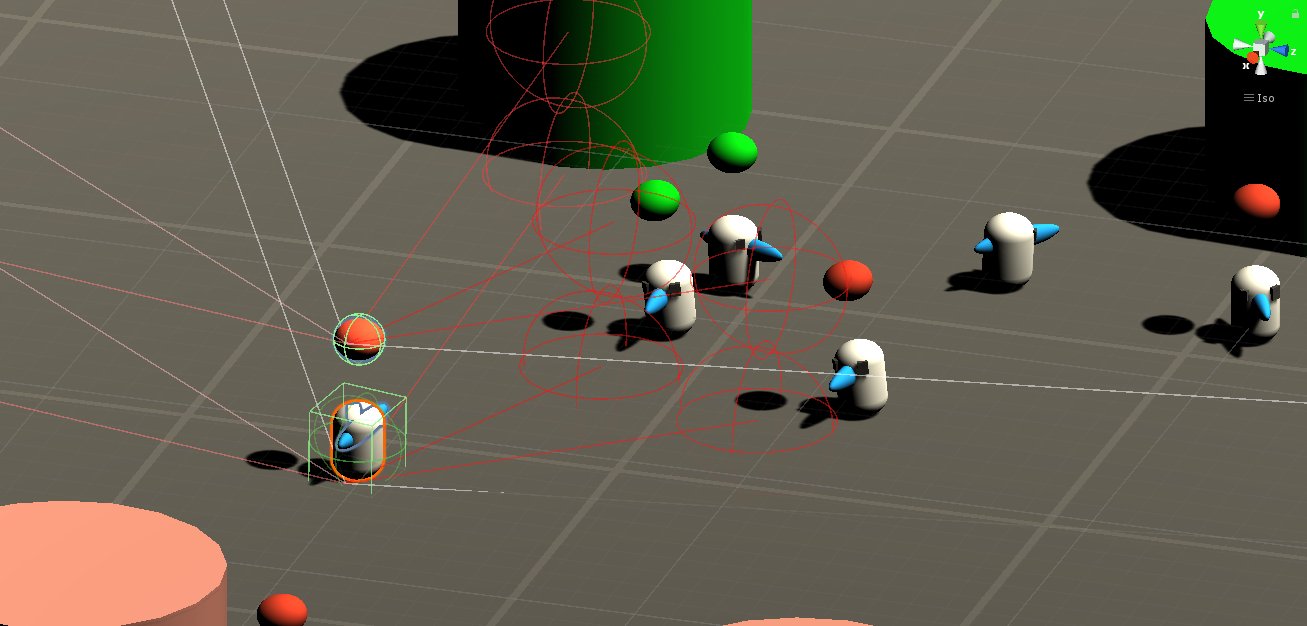

In most multi-agent settings it is necessary to let agents perceive information about each other. I achieve this by physically manifesting the agents “item_carried” state as a sphere that moves in sync with the agent at all times. I then allow other agents to perceive the state of their neighbors via a dual ray cast sensor. The upper tier ray cast detects only the arena walls and the item being carried (tagged sphere1/sphere2) above other agents (a total of 3 objects). The lower ray cast detects the source and sink boxes and other agents (3 objects). Each ray cast sensor comprises a vector \(V_{raycast-lower} \in \mathbb{R}^{35}\), \(V_{raycast-upper} \in \mathbb{R}^{35}\)

Fig. Agents use two-layer raycast percpetions in addition to their one-hot encoded ID and forward-facing vector. The top layer is able to detect the item carried by neighbors and the walls. The bottom layer detects the source and sink boxes and other agents.

Fig. Agents use two-layer raycast percpetions in addition to their one-hot encoded ID and forward-facing vector. The top layer is able to detect the item carried by neighbors and the walls. The bottom layer detects the source and sink boxes and other agents.

Finally, each agent receives its one-hot encoded ID: \(V_{ID} \in \{0,1\}^6\) and its forward-facing vector normalized to length 1: \(V_{forward} \in \mathbb{R}^3\). The forward facing vector acts like a compass and aids in agents orienting themselves. It may speed up learning of good policies; however it leads to inflexible behavior when the environment is changed (see Results).

Ultimately all observations are concatenated and fed to a neural network with 4 densely connected layers. The system was trained with 6 agents but many of my results use only 4 during inference without a significant decrease in performance.

{

sensor.AddObservation(transform.forward);

sensor.AddOneHotObservation((int)item_carried, 3);

sensor.AddOneHotObservation(ID, 6); //"ID" can be changed to a specific value e.g 1 to force all agents to act like agent 1.

}

Actions

Agents use a multi-discrete action space with 2 action branches. This allows them to select one action from each branch at the same time step and then do both.

branch 0: \(\{0, 1\}\) = {no movement, move forward} (by some increment)

branch 1: \(\{0, 1, 2\}\) = {no rotation, rotate counterclockwise, rotate clockwise} (by some increment)

public override void OnActionReceived(float[] vectorAction)

{

var forward_amount = vectorAction[0];

var rotationAxis = (int)vectorAction[1];

var rot_dir = Vector3.zero;

switch (rotationAxis)

{

case 1:

rot_dir = Vector3.up*1f;

break;

case 2:

rot_dir = Vector3.up*-1f;

break;

}

transform.Rotate(rot_dir, RotationRate * Time.fixedDeltaTime, Space.Self);

rb.MovePosition(transform.position + transform.forward * forward_amount * speed * Time.fixedDeltaTime);

AddReward(-1f / maxStep);

}

Results

Scaling the game: Including more agents increases performance

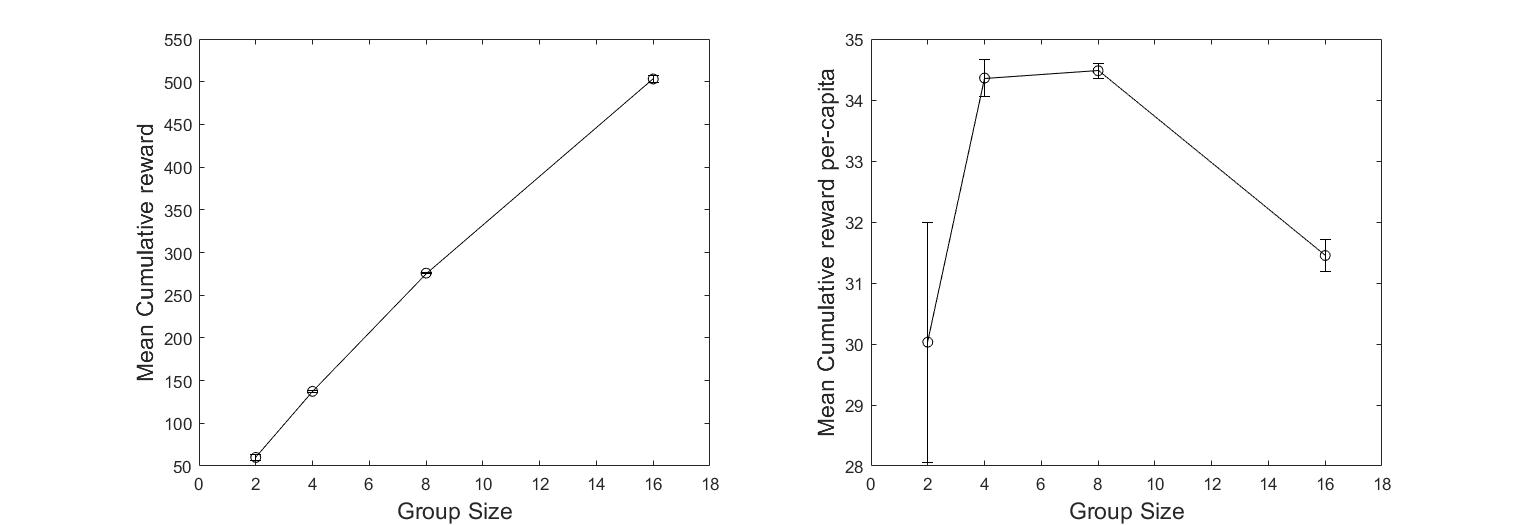

Agent behavior is robust to scaling the group size under the range I tested. In order to deploy more agents than 6, I simply set all agent IDs = 0 (for all group sizes). Making all agents identicle did not significantly affect their performance.

The per-capita cumulative reward per episode declines beyond a group size of 8. Overcrowding might be decreasing mobility.

Fig. Mean per-episode cumulative reward over all agents (left) and on a per-capita basis (right). Mean \(\pm\) standard error shown.

Fig. Mean per-episode cumulative reward over all agents (left) and on a per-capita basis (right). Mean \(\pm\) standard error shown.

Changing the environment leads to task failure

When the source and sink boxes are position-swapped, the agents fail to adapt (gaining little reward per episode). The agents’ observation included their own forward facing vector, which provides information on their orientation within the space. It is likely that this observation accelerated training. However, generalization ability could be enhanced by removing it.

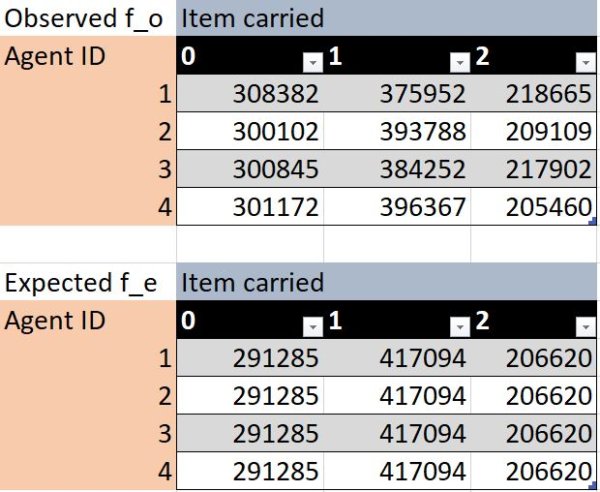

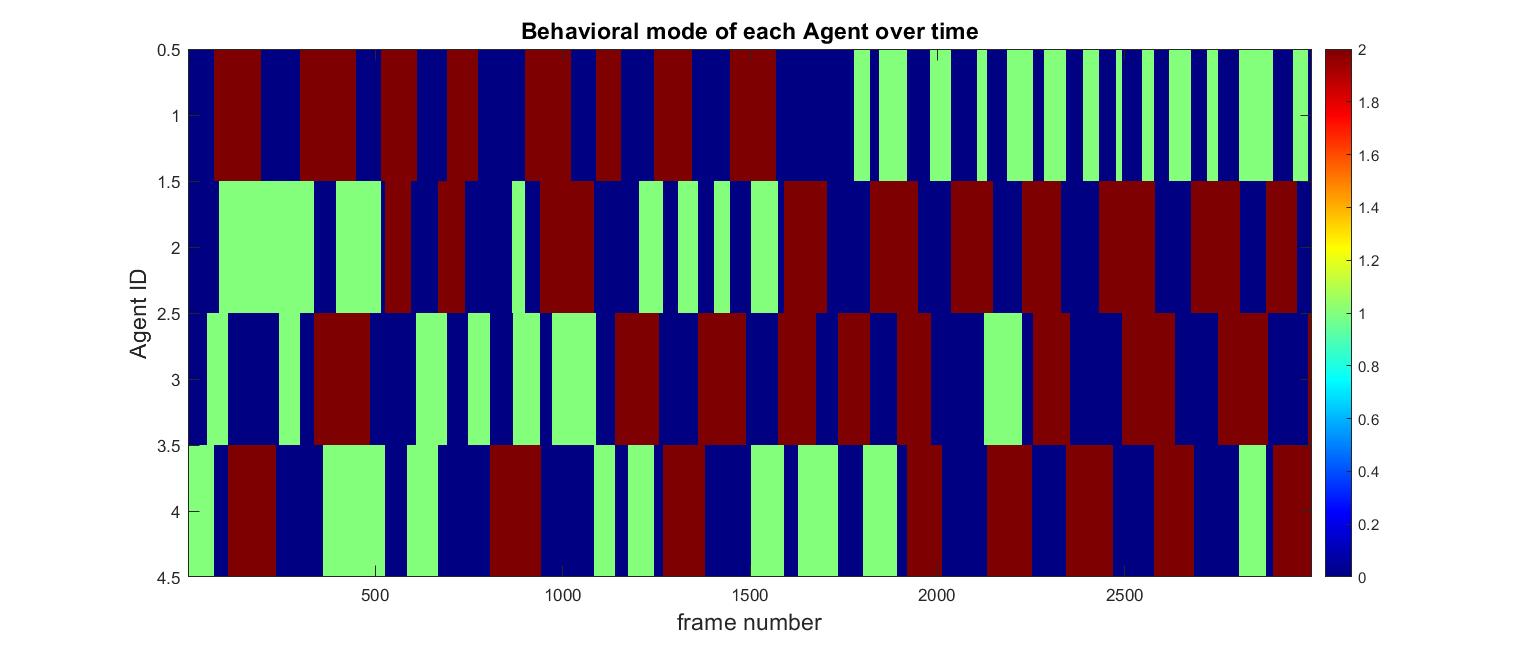

Partially unshared parameters led to (mildly) increased specialization

There were detectable but small differences in the behavior of agents with different IDs. The table shows the number of timesteps that each agent spent carrying each item. This is a simple way to quantify the difference in preferences for behavioral modes or tasks. A chi-squared test of independence showed a significant relationship between the ID number and item-carried \(\chi^2(6, N=3611996 (300 episodes)) = 1425, p<2E-16\). This means the proportion of time spent in each mode differed significantly between agents.

Fig. Observed \(f_o\) and expected \(f_e\) frequencies of timesteps each agent spent carrying each item. Expected is computed assuming independence of the variables.

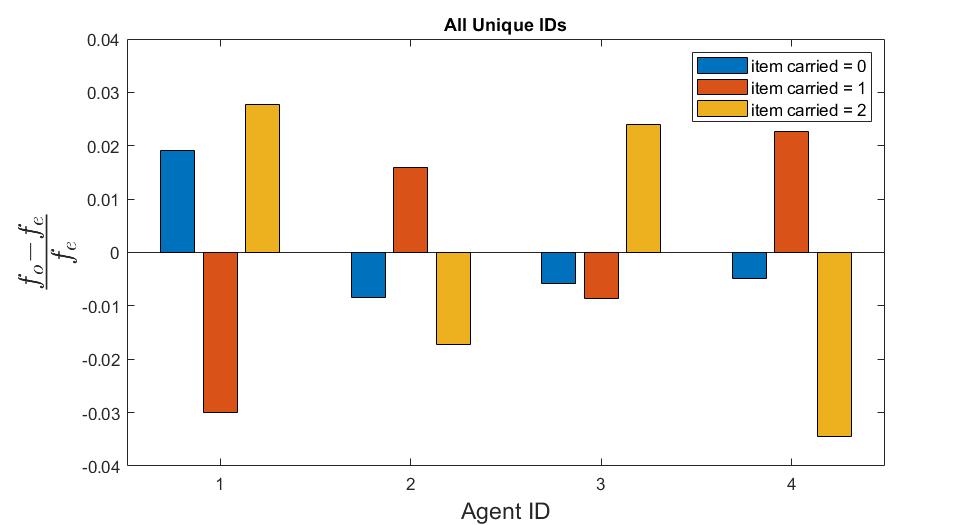

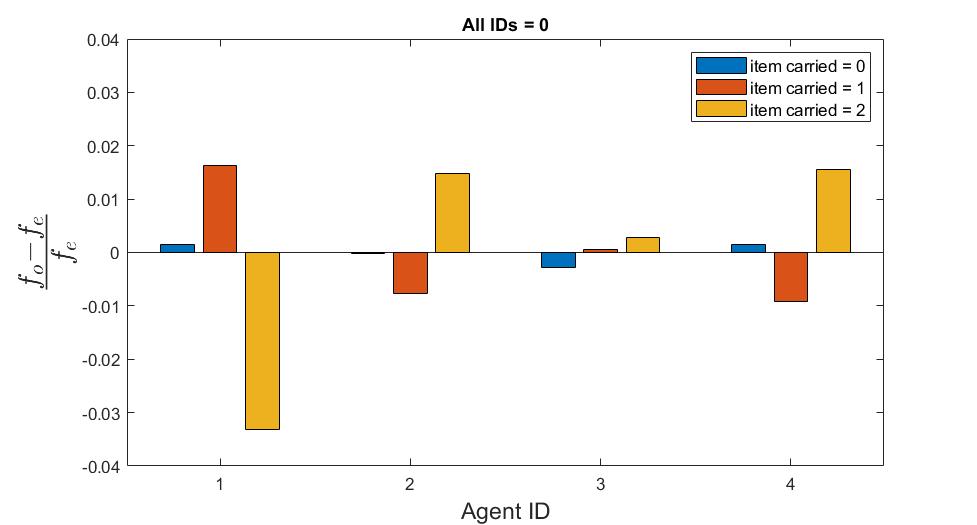

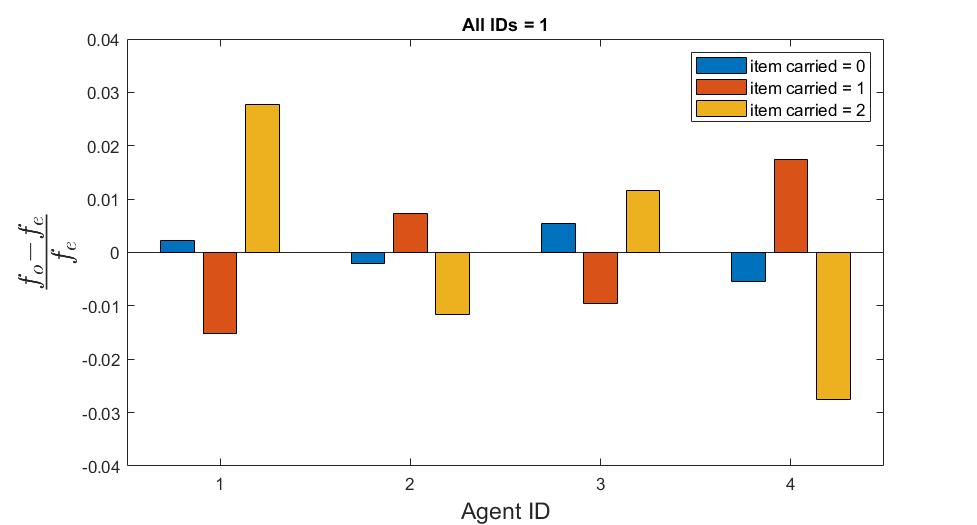

Surprisingly, I found that when making all agent ID’s identicle (using the same neural network, but providing the same ID as input to all agents), there is still a significant irregularity in the proportions that each agent spent in each mode. When all agents IDs are set to 0, \(\chi^2(6, N=3611996 (300 episodes)) = 489, p<2E-16\). When all agents IDs are set to 1, \(\chi^2(6, N=3659996 (300 episodes)) = 674, p<2E-16\). This suggests a natural variation in agents’ roles between episodes.

Fig The fractional difference in observed behavioral mode frequencies from expected frequencies. Positive/negative values indicate the agent performed that mode more/less often than what would be expected under the assumption that the frequency of a mode is independent of the agent. Top: all IDs are unique (=0,1,2,3), middle: all IDs set to 0, bottom: all IDs set to 1.

Fig The fractional difference in observed behavioral mode frequencies from expected frequencies. Positive/negative values indicate the agent performed that mode more/less often than what would be expected under the assumption that the frequency of a mode is independent of the agent. Top: all IDs are unique (=0,1,2,3), middle: all IDs set to 0, bottom: all IDs set to 1.

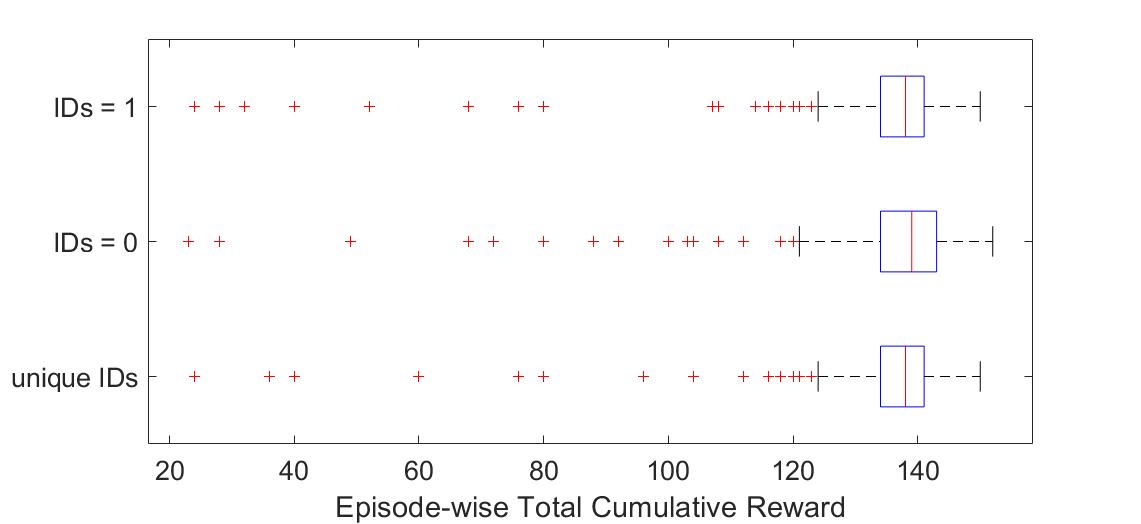

Group performance did not benefit from increased specialization

As in the previous result, I tested the condition of forcing all IDs to be A) unique (0,1,2,3), B) all equal to 0, and C) all equal to 1. Allowing agents to exhibit their slightly different behaviors did not improve performance.

Fig. Distribution of cumulative rewards (over all agents within one episode). Each point represents reward for one episode. N=300 episodes.

Fig. Distribution of cumulative rewards (over all agents within one episode). Each point represents reward for one episode. N=300 episodes.

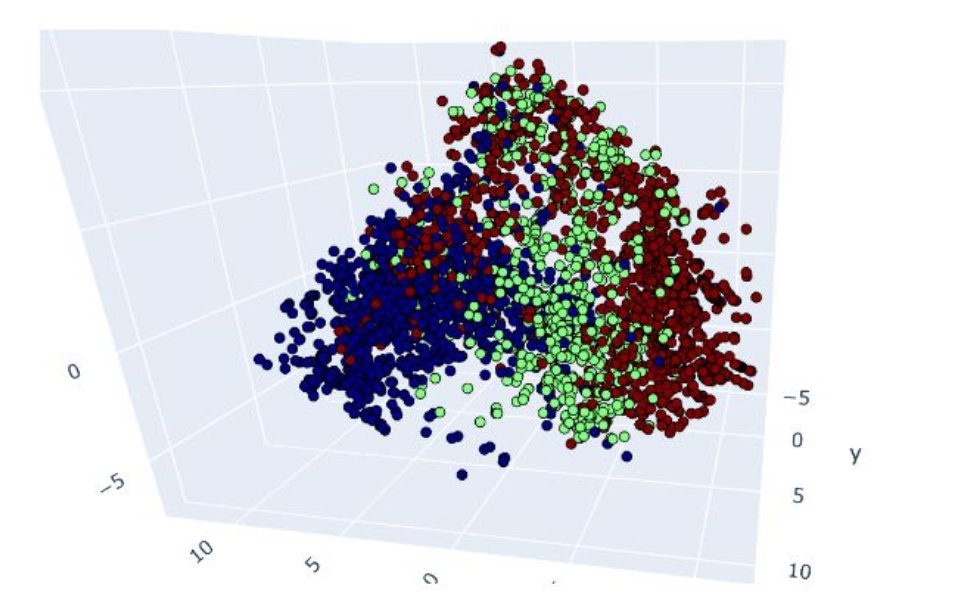

The three behavioral modes shown by the observation vectors’ data manifold

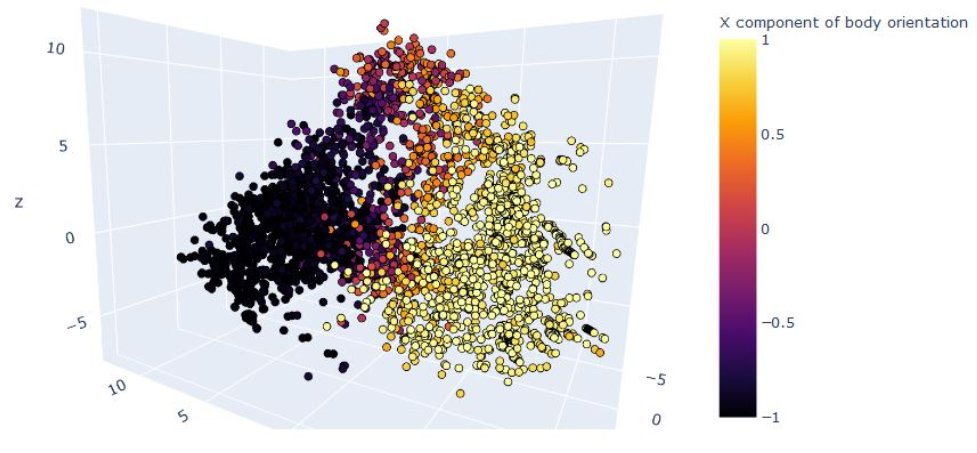

To create a more rich representation of the distinct behavioral modes, I extracted each agent’s observations over the course of a single episode. I then used isomap to perform dimensionality reduction on this data. I found that parts of the agent’s trajectory when it was carrying different items lied on different sections of this observation data manifold (Fig.). The agents were also moving in opposite directions during the item-carried=0 and item-carried=2 modes, in order to receive and deliver the items properly.

Fig. Each point represents one observation of one agent during a single episode containing 4 agents. Red: carrying item 2, green: carryin item 1, blue: empty-handed.

Fig. Same data as above, viewed from the same angle, but colorized by the x component of the agent’s forward-facing vector. Agents were moving towards the sink box (+x) when carrying item 2 and moving towards the source box (-x) when empty handed in order to obtain a new item 1.

Discussion and Conclusion

While I had suspected that providing ID numbers would cause agents to learn different policies, these policies were not different enough to cause agents to specialize strongly on any particular behavior. This makes sense considering that there is no real benefit to developing different behaviors in this problem. There is no clear advantage gained by having a preference for actions that would lead to one type of behavior over the other.

Fig. Item-carried over time for each of the 4 agents in inference mode. The pattern of switching tends to be chaotic and lacks any periodicity.

Fig. Item-carried over time for each of the 4 agents in inference mode. The pattern of switching tends to be chaotic and lacks any periodicity.

The overall behavior is more “messy” than I had predicted. With a set of 4 agents, you could imagine an optimal solution to this problem in which agents form an ocillatory pattern. Two of the agents might consistently grab item 1, pass it, and then walk back to the source box and repeat. The other two could then focus on receiving item 2 and depositing it in a repeating cycle that is matched in phase with the first two agents.

This does not happen; the agents actions are noisy and not always perfect. This makes them look a lot more like a real-life group of people trying their best to coordinate themselves. Despite being far from a mathematically perfect cycle, a system like this is probably much more adaptive. Embracing that chaos is a positive step towards intelligent multi-agent systems.