Why Specifying group objectives is powerful

One of the key advantages of deep reinforcement learning over explicit, or hand-coded, behavioral design (for e.g. agent-based modeling) is the ability to specify abstract objectives such as winning a game or solving a maze. It’s often advised to design reward functions based on the desired ultimate outcomes, as opposed to rewarding behaviors or subtasks you think may lead to those outcomes.

In a similar vein, I suspected that it might be possible to administer abstract group-level rewards in a multi-agent reinforcement learning scenario. Understanding how to do so could be immensely powerful for two reasons:

- Groups of interacting agents can work cooperatively to solve inherently distributed tasks such as construction and search.

- We generally know how to specify the desired outcome of the group, yet it is hard to know what constitutes behaviors that work toward this outcome.

To illustrate the second point, consider the group task of building a pyramid brick by brick. Assume each agent has the ability to pick up, move, and then place a brick in a 3D environment. You could imagine constructing some metric of success in terms of the geometry of the structure built. However, it is not at all clear what a given agent (with only locally available information) should be observing. Nor is it clear what types of actions to reward if you are doing reward shaping.

Is the notion of a “Group-level reward” possible in practice?

I define a group-level reward as a reward which is computed and triggered as a function of the group’s holistic state, as opposed to the state or action of any one particular agent in a multi-agent deep reinforcement learning setting. The indirect nature of this kind of reward signal makes it seem implausible that it could lead to any useful learned behaviors. In the pyramid construction example, the group reward could be a function of the squareness of the base and the triangularity of the sides, and it could be delivered (to all agents simultaneously) at either regular intervals or when some dramatic improvement was made. This doesn’t seem like it could work. At any given time there may be several agents who are not doing any actions in favor of the group objective. Why then would you reinforce those un-helpful actions?

Thermoregulators model: simplest possible demonstration of group-level rewards

In this project I show that agents can learn to act towards group objectives when the reward signal received is only peripherally related via group-level outcomes.

I imagine a group of 6 agents who are tasked with maintaining their group mean temperature \(T_g\) at a certain target temperature \(T_0 = 0\). Each agent is able to shift her own temperature \(T_p\) either up or down by a fixed increment per timestep.

I train the agents with a discrete action space \(\{-1, 0, 1\}\) corresponding to stepping down, not moving, and stepping up on the y-axis. Movement is restricted to the y axis, and height visualizes temperature. The plane corresponds to \(y=0\). The reward signal is defined as

\(R(T_g) = 0.25* 4^{1-\beta|T_g - 0|}\) (\(\beta = 0.2\))

I train the agents with a discrete action space \(\{-1, 0, 1\}\) corresponding to stepping down, not moving, and stepping up on the y-axis. Movement is restricted to the y axis, and height visualizes temperature. The plane corresponds to \(y=0\). The reward signal is defined as

\(R(T_g) = 0.25* 4^{1-\beta|T_g - 0|}\) (\(\beta = 0.2\))

which approaches 0 as \(|T_g| \rightarrow \infty\) and approaches 1 as \(|T_g| \rightarrow 0\). This reward is given every time an agent requests an action in Unity ML-Agents (which is at a fixed interval):

public override void OnActionReceived(float[] vectoraction)

{

if (vectoraction[0]==1)

{

transform.position = transform.position + new Vector3 (0, deltaT, 0);

}

else if (vectoraction[0]==2)

{

transform.position = transform.position + new Vector3 (0, -deltaT, 0);

}

T_group = GetMeanTemperature();

AddReward(0.25f*(float)Math.Pow(4f, 1f - Math.Abs(T_group - T_target)*beta)); //group level reward!

AddReward(-1f / maxStep); //existential reward

}

public float GetMeanTemperature()

{

T_group = 0;

GameObject[] agents = GameObject.FindGameObjectsWithTag("agent");

foreach (GameObject p in agents)

{

T_group += p.GetComponent<Thermo_agent>().transform.position.y;

}

return T_group/N_agents;

}

The important thing to note is that the reward is not triggered as a direct result of any particular condition satisfied by the agent. It is delivered automatically each time step.

Observation Space

I tested 3 types of observations. These are each fundamentally different types of information that an agent can use to decide an action. My goal was to determine which of these leads to the best performance.

- \(T_p\) (agent perceives their own temperature)

- \(T_g\) (agent perceives the group mean temperature)

- \([T_p, T_g]\) (agent perceives both)

Case 3 is below:

public override void CollectObservations(VectorSensor sensor)

{

sensor.AddObservation(Mathf.Clamp(GetMeanTemperature()/40, -1, 1)); //group level observation

sensor.AddObservation(Mathf.Clamp(transform.position.y/40, -1, 1)); //individual level observation

}

The model is trained with PPO using Unity’s ML-Agents kit. You can find my repository here

Results

The impact of observation type

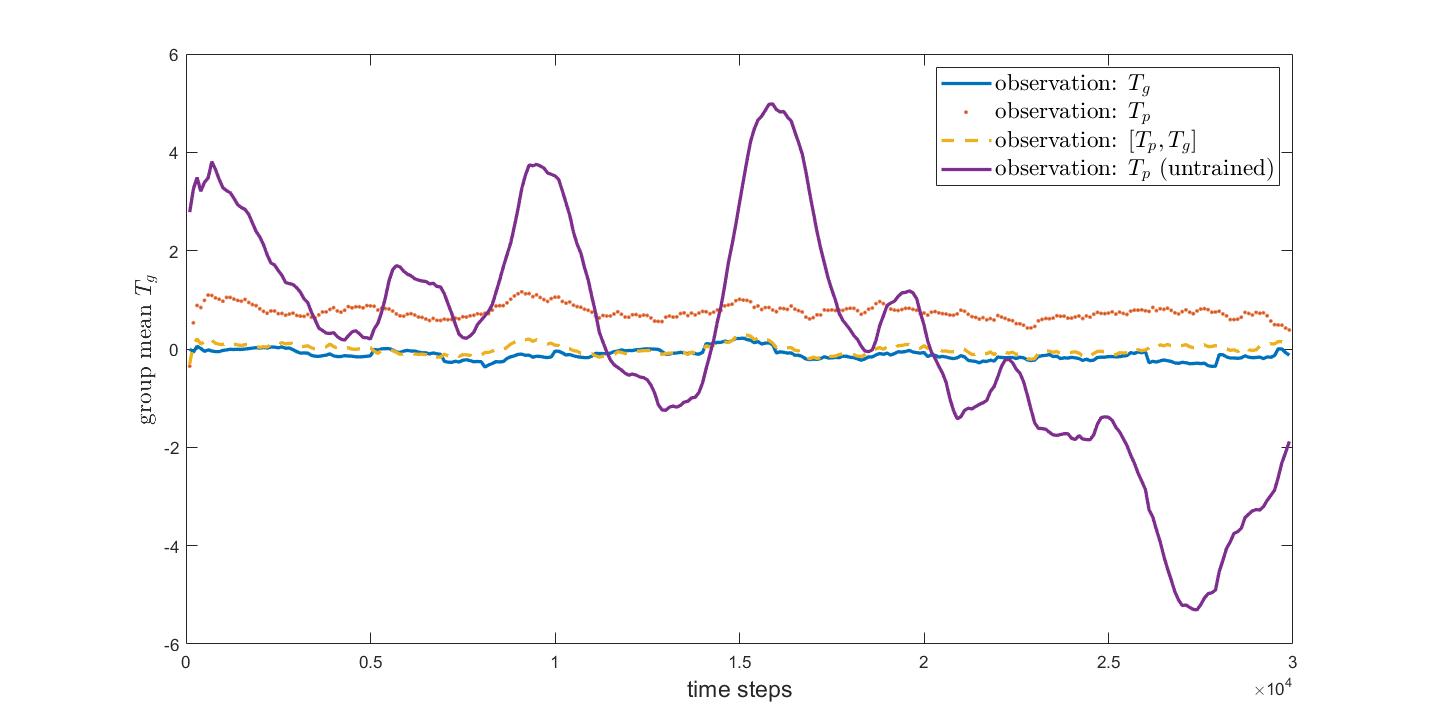

I found that the agents were able to learn to maintain a stable \(T_g\) relative to untrained agents, under all observation types. However, the distribution of temperatures varied between observation types.

Group Mean \(T_g(t)\)

- Agents trained using \(T_p\) as input (orange dots) remain in a tight cluster, but their mean is biased toward positive values. I found this was consistent across multiple episodes.

- Agents trained using \(T_g\) as input (blue line) showed no bias, but over time developed a large variance among group members. Their \(T_g\) remained very close to 0 dispite the large spread, indicating they had successfully learned to adjust position to compensate for other members diverging away from 0.

- Agents trained using \([T_p, T_g]\) (dashed yellow line) both maintained a \(T_g\) near zero, while having relatively low variance in temperature.

- Untrained Agents (random actions) (purple line) exhibit large fluctuations in temperature.

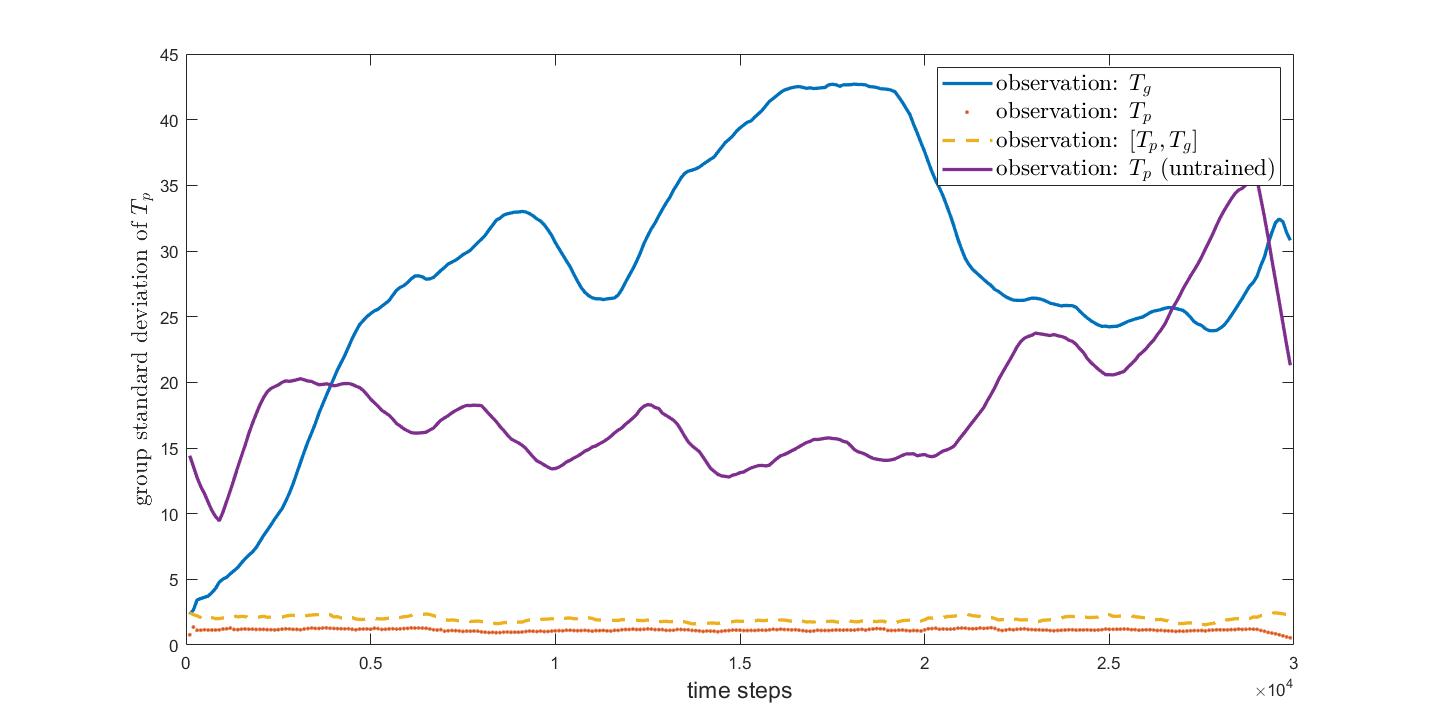

Standard Deviation of \(T_p\)

Conclusion

I have demonstrated that agents in a simple multiagent RL setting can learn beneficial actions from a reward signal that is delivered only on the basis of group-level outcomes. Agents in this problem setting must effectively learn by by proxy in that they are rewarded when other group members have done useful actions. Many actions having little to do with the group objective inevitably end up being rewarded and thus reinforced. Over the course of training, this source of error was apparently overcome. This opens the possibility of extending the technique of group-level rewards or rewards-by-proxy to more complex group objectives.

The result on the choice of observation space demonstrates that a kind of bias-variance tradeoff can emerge if each agent’s \(T_p(t)\) is seen as a predictor of the target temperature. I found that providing information on both one’s own state (individual level) and the group state allowed the group to stabilize its mean about an accurate temperature (i.e. near \(T_0\)) while its individual members had minimal variance.